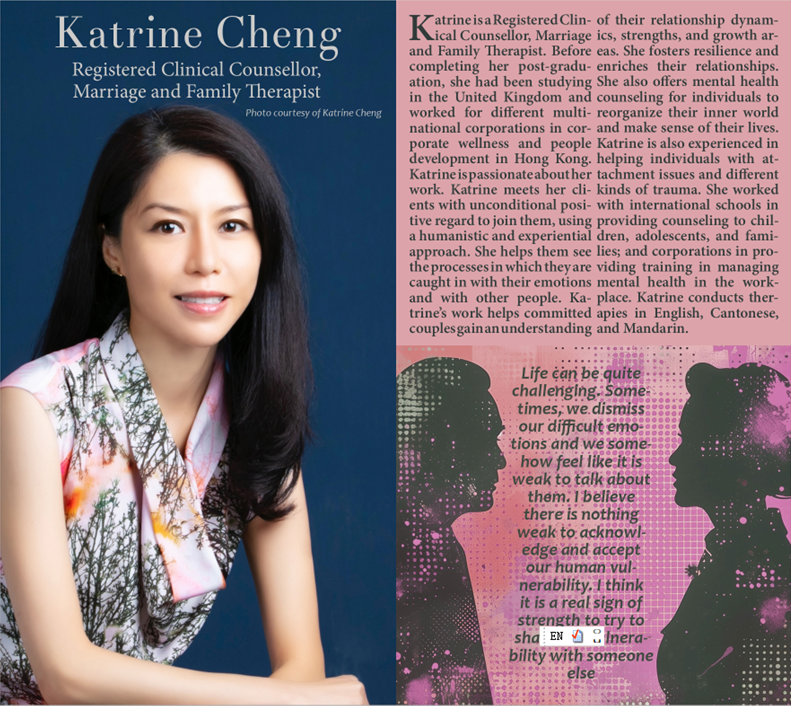

When my mother had a stroke, she did not have any of the usual risk factors – she was not obese, did not have high blood pressure, atrial fibrillation (irregular heartbeat), nor high cholesterol. I asked her neurologist what the likely cause was. His answer: depression. “She sat too still for too long, a clot formed and caused her stroke,” he said. I should not have been surprised. A recent and large study suggests people with depression and/or anxiety have a higher risk of developing one or more of 29 other health conditions. They range from heart disease to diabetes, bacterial infections to chronic obstructive bronchitis, osteoarthritis and diseases of the circulatory system and blood. Dr Philipp Frank of the University of London’s Institute of Epidemiology and Health Care, one of the study authors, says research that aims to understand the nature of the relationship between depression and physical illnesses has usually looked at it from two perspectives. One suggests that depression may develop in response to psychological, biological and social changes. The other suggests that depression itself may be an independent risk factor for developing physical illness. “Our findings support this – we found that people who were hospitalised due to poisonings, falls, diseases or symptoms of the circulatory, respiratory, digestive, and musculoskeletal systems, and severe infections, were more likely to develop depression compared with individuals who had not been hospitalised due to these conditions,” Frank says. There is also growing evidence that suggests depression may act as an independent risk factor for distinct physical illnesses. “We found that individuals with moderately severe or severe depression have at least a 1.5 times higher risk of developing 29 different conditions affecting multiple organs.” “If there is a particular situation that is affecting your mental well-being, the best thing to do is to seek specialist practical help to resolve the problem Katrine Cheng, therapist at Mindbloom Hong Kong This finding suggests that the impact of depression on physical health is widespread and not limited to a specific area of the body or particular group of diseases, Frank says. The risk can be much higher for some diseases. People who suffer with depression were found to be seven times more likely to be admitted to hospital because of endocrine and related internal organ diseases, such as diabetes or obesity, than because of mental or behavioural disorders. While the study did not explore why serious mental illness might affect physical health and make a person vulnerable to disease, other studies have suggested several plausible mechanisms, Frank says. These include lifestyle behaviours such as smoking, alcohol consumption and unhealthy diet, as well as exposure to sustained increased levels of the stress hormone cortisol, for example. Frank says research shows that treating depression effectively may help to reduce the negative physical health consequences associated with the condition. Therapist Katrine Cheng at Mindbloom in Hong Kong, a member of the Hong Kong Professional Counselling Association, agrees that it’s important to seek help quickly if a person is battling depression and/or anxiety – which, she says, are not separate. They occur together much of the time, and one is often a risk factor for the other. “If there is a particular situation that is affecting your mental well-being, the best thing to do is to seek specialist practical help to resolve the problem,” Cheng says. “If someone close to you has died and you are struggling to cope, you may want to talk to a bereavement counsellor. “If you have been unemployed for a long time and this is affecting your mental health, you may want to talk to a career adviser. “Or if you have legal, money or housing problems that are causing your stress or anxiety, you may find it useful to talk to the Social Welfare Department.” None of those issues start out as an illness. But because they affect the way we feel, they can create anxiety, which can lead to depression – which can be the catalyst for mental and physical illness. There are many different kinds of therapy and it’s a question of identifying one that works for you – cognitive behavioural therapy, emotionally focused therapy, or family (systemic) therapy, for example. Medications may also help. “These drugs don’t cure mental health problems, but aim to ease the most distressing symptoms,” Cheng says. “They may give sufferers a reprieve to find the right therapy to help them build the tools they need to cope.” Cheng urges family members to support sufferers by listening to them and encouraging them to get the needed support – and to listen some more to help them avoid a relapse. A number of study participants had recurring episodes of depression. Keep an eye on people with depression to see that they are responding to treatment, and support them in developing a relapse-prevention plan. Self-care when struggling with mental illness – exercising, eating properly, not drinking too much alcohol, getting good quality sleep, managing stress – is a huge challenge. Frank stresses the need to be mindful of, and manage, physical health conditions that put you at higher risk for developing depression, particularly high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and obesity. |